Amerasia

Building this gigapixel scan of an ancient map by cartographer Caspar Vopel was as fun as it gets! This project was the brainchild of Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel from the Institute of Fine Arts.

Amerasia

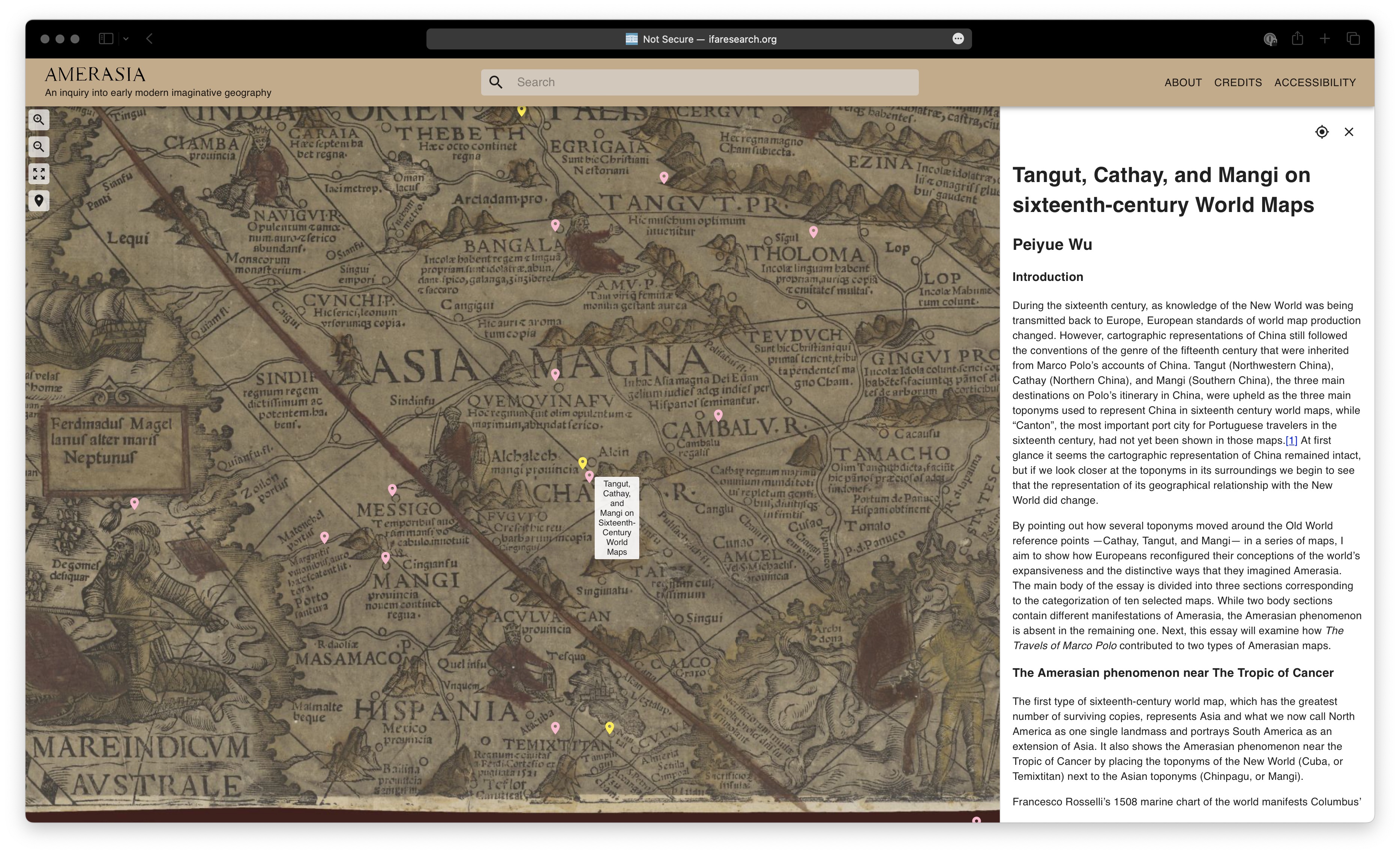

In Renaissance Europe, many people, including most mapmakers, believed that Asia and America overlapped on the same landmass. While some cartographers experimented with separating the Asian and American lands in the second half of the sixteenth century, their maps were distinctly in the minority. Most cosmographers continued to see the New World extending from America to Asia, a continuum articulated by both landmasses and archipelagoes of islands. The persistent connection between Asian and American New Worlds colored the way Europeans saw the inhabitants of these regions, as well as the products, both natural and man-made, that streamed into Europe from Asia and America, sometimes through Africa. Early modern European cartographers, writers, editors, and artists systematically blurred Asia and the Americas, placing Asian ports in Latin America, showing Marco Polo`s elephants in Canada, dressing the inhabitants of India in Ameican feathers, labelling Mixtec screenfolds as Chinese, and identifying Aztec temples as mosques.

The associations between America and Asia that dominated the geographical and cultural imagination of Europe for two centuries after 1492 pose a fundamental conceptual challenge, making it necessary to suspend the definition of the words ”America” and ”Asia” and imagine an early modern ”Amerasia.” Even when it became common to separate the continents on maps, copious themes of Amerasian thinking remained in place. Amerasia is like a lost continent, consigned to oblivion after modern ways of organizing and imagining the world took hold especially from the eighteenth century. This web portal aims to bring the Amerasian worldview back to life for contemporary readers.

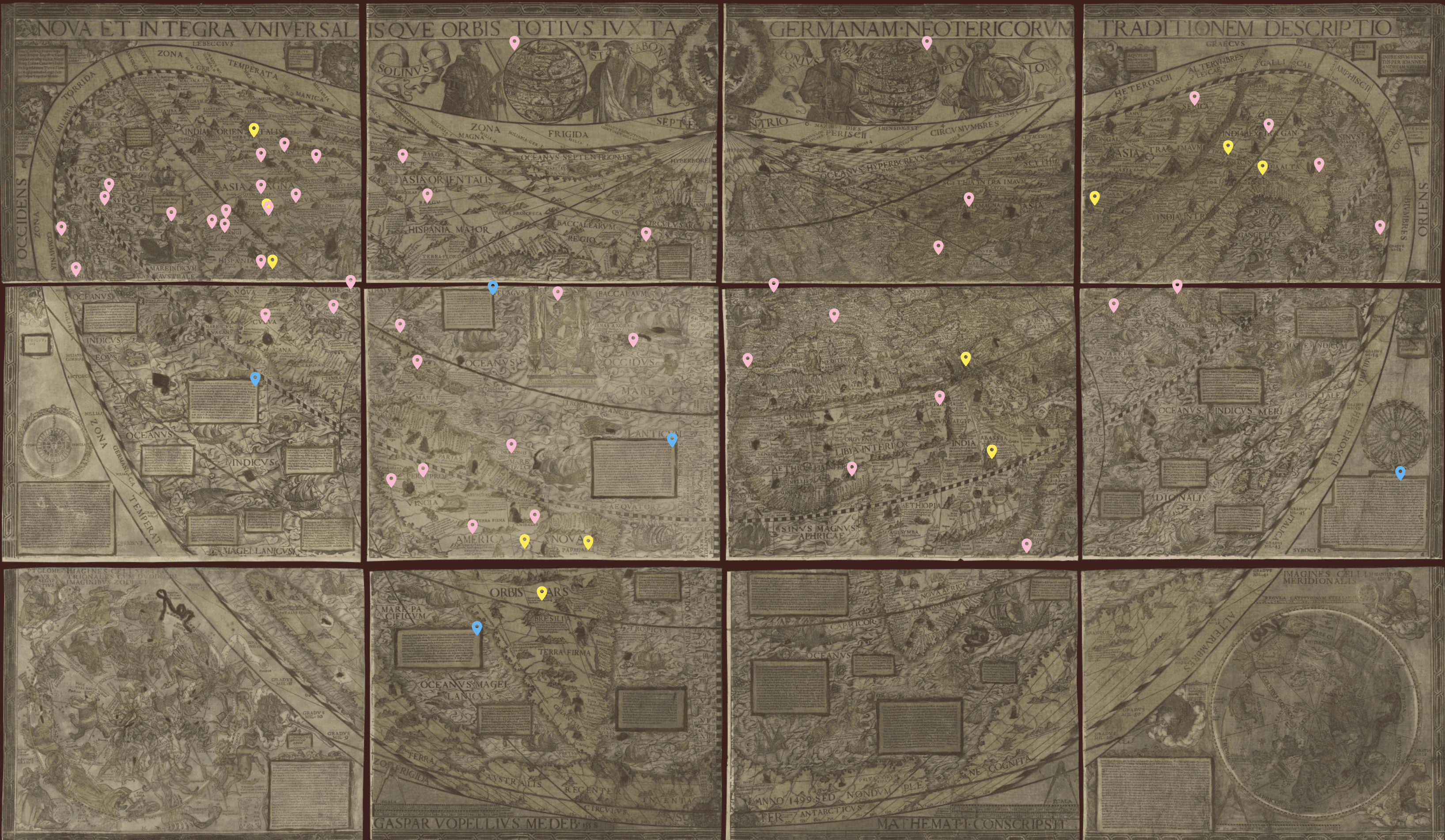

In 1545, the German mathematician and cartographer Caspar Vopel (1511-1561) designed a famous and influential map of the world that spectacularly embodies the Amerasian worldview. Vopel’s original is now lost, and we know it through a reprint made by Venetian printer Giovanni Andrea Vavassore in 1558, a large-scale, woodblock-printed wall map in twelve sheets entitled A New Complete and Universal Description of the Whole World According to the Modern German Tradition (NOVA ET INTEGRA VNIVERSALISQVE ORBIS TOTIVS IVXTA GERMANVM NEOTERICORVM TRADITIONEM DESCRIPTIO).

Although well known in its time, today a single copy of the Vopel/Vavassore map survives in the Houghton Library at Harvard University. Using an interactive, high-definition interface, this website explores the map’s content—its toponyms, cartouches, figurative images, and textual descriptions—amplifying the map through a wide-ranging explanatory apparatus. Pink pins offer short entries about locations on the map, blue pins indicate translated cartouches, and yellow pins offer more extended essays pegged to sites and inscriptions with particular Amerasian significance.

In the spirit of the National Endowment for the Humanities Collaborative Fellowship that supported its creation, we present this online platform for the Vopel map as an invitation to collaborative scholarship. We invite additional entries on toponyms or themes relevant to the Amerasia problem, hoping that this new digital tool encourages an accelerated and dynamic scholarly exchange.

-Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel

To read more about Amerasia, see Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel, “Amerasia: European Reflections of an Emergent World, 1492-ca.1700,” Journal of Early Modern History 23 (2019): 257-295.